Long-term interest rates are on the rise. The 10-year US Treasury bond yield, which had fallen below 1.5 percent this past summer and still stood at 1.75 percent just one month ago, is now approaching 2.5 percent. Since interest rates on bank deposits and loans tend to move together with those on government bonds, these higher yields will help many Americans, who will now earn more on their savings, at the same time they increase costs for others, who plan to borrow to purchase new homes and cars. On balance, however, rising long-term interest rates provide a welcome sign that the economic recovery remains intact and that the lasting effects of the financial crisis and Great Recession of 2007-09 continue to fade.

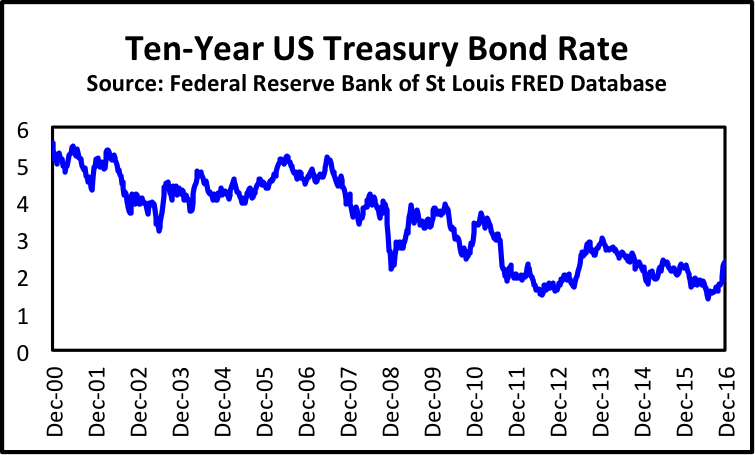

The graph below plots the 10-year Treasury bond rate over a period that extends back before the previous recession, in 2001, to put the most recent increase in yields in proper perspective. From this view, the question is not why long-term interest rates are so high today, but instead why they have been so low since the crisis. To answer this question, it is helpful to recognize that modern theories of asset pricing measure the riskiness of any long-lived capital asset based not so much on the volatility of its returns, but instead based on how its returns covary with overall economic and financial conditions.

Most individual stocks, and the stock market as a whole, provide high returns during good economic times while exposing their holders to significant losses during bad times. According to theory, investors demand – and receive – high returns from stocks on average precisely because share prices decline in value during recessions, exactly when those losses hurt the most. By contrast, gold is a risky commodity investment, but one that tends to do well during periods of turmoil and crisis. Precisely because it acts as a hedge against disaster, investors are willing to own gold even though, on average, it provides returns far below those offered by stocks.

The task of applying this theory to long-term government bonds starts by observing that unlike stocks, which pay uncertain dividends, U.S. Treasury bonds make payments of interest and principle that are fixed and known, in dollar terms, in advance. The risk embedded into long-term bonds, therefore, stems from the possibility that unanticipated changes in economy-wide inflation will affect the purchasing power of those known dollar payments. Unexpectedly high inflation erodes the value of the fixed payments made by bonds, while unexpectedly low inflation – and especially unexpected deflation – increases the value of those same fixed cash flows.

This process through which nominal, or dollar-denominated, payments are translated into real, or inflation-adjusted, returns is key to interpreting movements in bond prices and yields. If bad economic times are associated with higher inflation, as they were during the “stagflationary” era of the 1970s, long-term government bonds become risky assets, similar to stocks, that pay off poorly exactly when that hurts the most. On the other hand, when bad times are associated instead with low inflation or deflation, as they have been more recently, bonds become hedges like gold, that pay off unexpectedly well just when those extra payments help the most.

In the technical language of modern finance, the “beta” of long-term bonds, measuring their covariance with overall economic conditions, appears to vary over time and, in particular, seems to have flipped from being positive in the 1970s and 1980s to negative in recent years, a phenomenon studied in more detail in recent papers by John Campbell, Adi Sunderam, and Luis Viceira at Harvard University and my colleague Dongho Song at Boston College.

Therefore, under conditions prevailing since the financial crisis, where the greatest macroeconomic risks are those of a prolonged period of deflationary stagnation, bond yields will fall or rise as these risks wax or wane. In particular, as worries over the threat of stagnation fade, investors’ will feel less urgency to hold long-term bonds as hedges; bond prices will therefore fall and bond yields will rise.

This brings us full circle, back to the idea that the recent run-up in long-term bond yields spells good news for the American economy, reflecting diminished risks of another deflationary recession. Since much of the recent increase in long-term yields has occurred over the past month, it is natural to assume that investors’ newly found optimism reflects the outcome of the November elections. Note, however, that the graph from above shows that long-term bond rates also moved higher towards the end of 2013, another period of renewed optimism that was followed by disappointing economic performance.

The new signs are welcome, but sustained improvement in financial conditions will only happen if the new Trump Administration follows through, cooperating with Congress to create a legislative and regulatory environment that is favorable to economic growth with low but stable inflation.

Peter Ireland is a professor of economics at Boston College and a member of the Shadow Open Market Committee.

Interested in real economic insights? Want to stay ahead of the competition? Each weekday morning, e21 delivers a short email that includes e21 exclusive commentaries and the latest market news and updates from Washington. Sign up for the e21 Morning eBrief.